COVID raised awareness of getting vaccinations and their importance in public health. But vaccinations aren’t just limited to pandemics. They are also vital for our general health and controlling what most people wouldn’t consider a major threat.

Vaccinations for influenza, commonly referred to as the flu, are vital for both protecting the NHS from hospitalisations but also protecting immunocompromised patients such as those with particular infections such as HIV and AIDS, those with diabetes, those undergoing treatment for a range of cancers, bone marrow or organ donors as well as older patients and those who’s health is compounded such as by poor living conditions such as mouldy homes already putting a strain on their bodies.

Personally, I’m in good health with a strong immune system, I’m a blood donor and a recent kidney donor so I know from blood works and other health tests that I’m at low risk from these more routine viruses, even testing positive for COVID twice and being asymptomatic. But in my roles, as volunteer ambulance crew and working in crowded shopping centres as well as with youth, I have a responsibility to ensure that everyone I’m exposed to is protected from any infections I may be carrying, whether I know it or not.

So how do vaccines work?

With COVID, a lot of people believed that a vaccine would provide complete protection, and when it didn’t people would argue that it was pointless to get one. But that’s not how a vaccine works.

When you are vaccinated against a particular virus, such as SARS-COV-2 which causes COVID-19 or H1N1 which caused swine flu, a vaccination will cause your body to produce antibodies which will allow the immune system to be ready to fight an infection removing the period of time needed to build antibodies from natural exposure. But this doesn’t mean you won’t become infected.

For the immune system to fight an infection, it first needs to be infected by that infection. Rather than prevent a host from being infected outright, the point of a vaccination is to (a) prevent the patient becoming severely ill, (b) being admitted into hospital and increasing the workload on the NHS which is already overtaxed and (c) it can help, though not guarantee, to prevent the infected host from passing the infection onto others by allowing the immune system to prevent the infection developing to the point of it being contagious. These are the points of a vaccination, not to provide a magic shield around the body preventing infection in the first place.

What vaccines are there?

There are hundreds of different vaccines available for a range of viruses.

Under the NHS, most of us will get a range of vaccinations as we grow up which provides protection to some of the most common infections including the likes of meningococcal, measles, mumps and rubella, hepatitis B, HPV, and the flu to name a few.

Are there risks?

There are risks associated with nearly anything. Vaccines are no different.

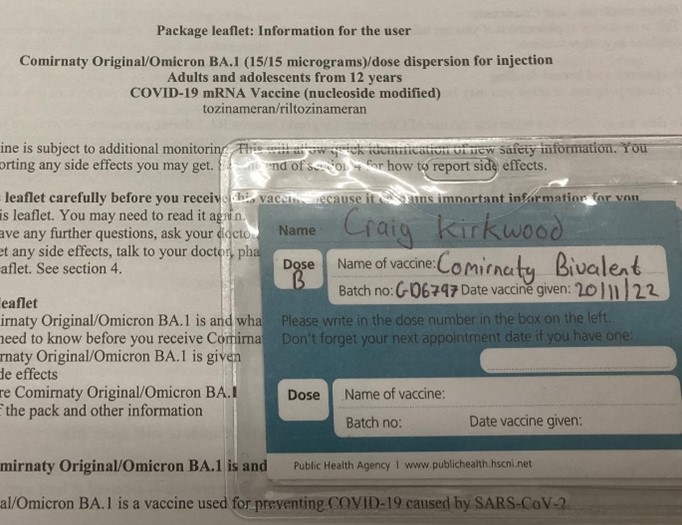

When you get a vaccination you will be given information on side effects and risks involved.

Vaccines tend to have similar risks, COVID for example would include a sore arm at the injection site, feeling tired and flu like symptoms. If you are someone who suffers from severe allergic reactions it may be suggested that you skip particular vaccinations as the risk of a reaction may out way the benefits, your GP or vaccinators will advise on this.

Is it worth being vaccinated?

According to the World Health Agency, a department of the Untied Nations, vaccinations save between two and three million lives each year.

Even if you’re not vulnerable to an infection, such as the flu, its still beneficial from a public health standpoint to be vaccinated as this reduces the likely hood of you passing an infection to others and reduces the workload on an already overtaxed NHS which has a knock-on effect on healthcare across the board.